The wind, love and other disappointments

Stephen Felton

Stephen Felton

2015 February 17

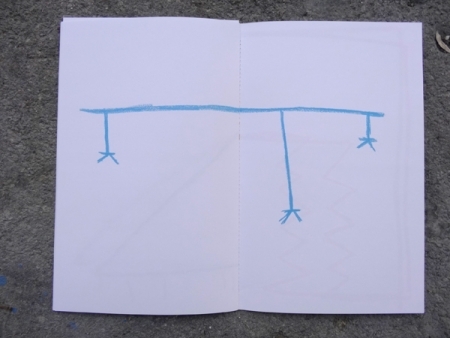

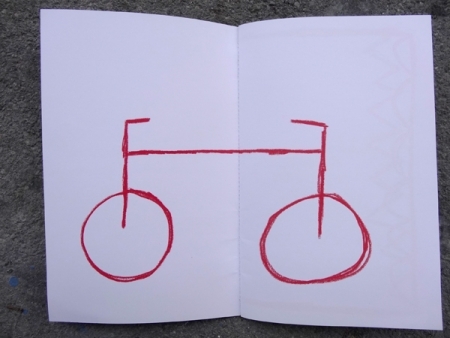

Seriously flippant, radically relaxed, awkwardly

15 CHF (13 EUR)

+ shipping SWISS 2 Europe 3 World 5 CHF

ADD TO CART

+ shipping SWISS 2 Europe 3 World 5 CHF

ADD TO CART

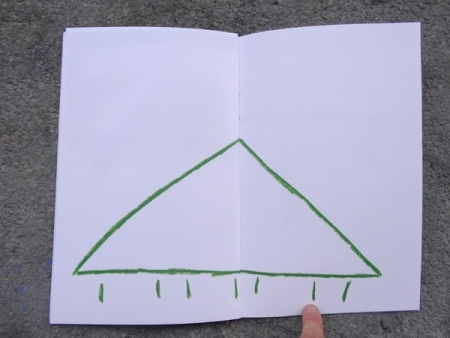

spontaneous, readily complex: such paradoxical

descriptions of Stephen Felton’s paintings are

disconcerting. Freehand drawings in a single colour on a

large canvas, and a simplicity of sign and its execution

that suggests children’s drawings, cave paintings and

blurred pictograms in which symbol and icon, figuration

and abstraction are indistinguishable – the birth and

death of the signifier all at once.

The main motifs in this economical iconography are

arrows, staircases, ladders and stars – for they resist

the habitual classifications of representation. Beyond

their semantic effectiveness, they above all reflect the

speed of a gesture. Detached from virtuoso authority, and

accessible to all, Felton’s painting expresses a certain

composure, a calm disrespect for whatever might be

thought of the painter’s profession and his various schools

– a meticulous, patient pursuit of sobriety and fragments

that would jar with the brisk language of figuration libre.

Yet we should not see this as some postmodern game

in which references are ironically erased. Felton’s work

displays a belief in the process of painting rather than

its completion. As the critic Jill Gasparina has written,

‘Assembling colours in a certain order on the flat surface

of a prepared canvas ... is not a way to obtain an artefact

fit to decorate an interior or occupy vacant space in an art

centre, but a total activity that organises the whole of life.’

Here painting is understood first of all as a banal activity,

on the same level as those that mark the artist’s everyday

life, subject to the whims of his moods, of time, the people

he meets and the things he reads.

The Wind, Love and other Disappointments, thus presents

a hitherto series inspired by Arno Schmidt’s novel Scenes

from the life of a faun. In this masterpiece of post-war

German literature we follow, in three chapters (February

1939, September 1939 and September 1944), the life

of Heinrich Düring, a public official in the small town

of Fallingbostel who is sickened to see Nazi stupidity

infiltrating people’s minds – including those of his own

wife and son.

He seeks refuge in the detailed study of village archives,

where he learns of the existence of a deserter from

Napoleon’s army who had once terrorised the area,

and actually finds his hiding-place, a shack in the midst

of the forest. The narrator turns this makeshift shelter,

unrecorded by surveyors, into a place of retreat and

remoteness from the world that finally allows him and his

lover to escape the Allied bombardments.

Günter Grass said of Schmidt ‘I do not know any writer

who has listened so closely to the rain, so often talked

back to the wind and given the clouds such literary

surnames.’ The novel combines an erudite, terse cynicism

with grand, elated outpourings about the moors, the moon

and the wind. In formal terms it consists of a succession of

short paragraphs full of neologisms, plays of punctuation,

onomatopoeic nouns and coded references, in a ‘narrative

cascade’ of memories and fleeting glimpses arranged ‘as

if a spasm-shaken man were watching a thunderstorm in

the night’.

We can imagine how this way of writing in accordance

with ‘the lines of movement and the tempo of the

characters in space’, in which all is fragments and speed,

had a special resonance with Stephen Felton. Taking

this mysterious book, which he only knows in English

translation, he in turn presents a series of forms that do

not necessarily illustrate a particular passage, but instead

reflect a memory of his readings, his daydreams and the

dreamlike fertility of a literary experience.

Paul Bernard

Curator at Mamco

Translation, Kevin Cook

descriptions of Stephen Felton’s paintings are

disconcerting. Freehand drawings in a single colour on a

large canvas, and a simplicity of sign and its execution

that suggests children’s drawings, cave paintings and

blurred pictograms in which symbol and icon, figuration

and abstraction are indistinguishable – the birth and

death of the signifier all at once.

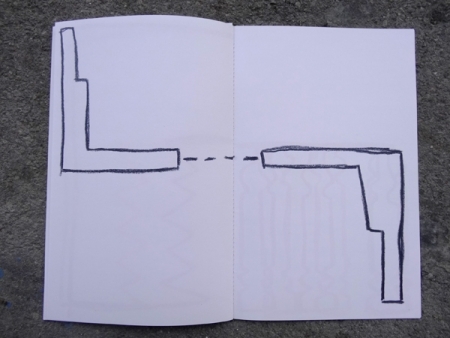

The main motifs in this economical iconography are

arrows, staircases, ladders and stars – for they resist

the habitual classifications of representation. Beyond

their semantic effectiveness, they above all reflect the

speed of a gesture. Detached from virtuoso authority, and

accessible to all, Felton’s painting expresses a certain

composure, a calm disrespect for whatever might be

thought of the painter’s profession and his various schools

– a meticulous, patient pursuit of sobriety and fragments

that would jar with the brisk language of figuration libre.

Yet we should not see this as some postmodern game

in which references are ironically erased. Felton’s work

displays a belief in the process of painting rather than

its completion. As the critic Jill Gasparina has written,

‘Assembling colours in a certain order on the flat surface

of a prepared canvas ... is not a way to obtain an artefact

fit to decorate an interior or occupy vacant space in an art

centre, but a total activity that organises the whole of life.’

Here painting is understood first of all as a banal activity,

on the same level as those that mark the artist’s everyday

life, subject to the whims of his moods, of time, the people

he meets and the things he reads.

The Wind, Love and other Disappointments, thus presents

a hitherto series inspired by Arno Schmidt’s novel Scenes

from the life of a faun. In this masterpiece of post-war

German literature we follow, in three chapters (February

1939, September 1939 and September 1944), the life

of Heinrich Düring, a public official in the small town

of Fallingbostel who is sickened to see Nazi stupidity

infiltrating people’s minds – including those of his own

wife and son.

He seeks refuge in the detailed study of village archives,

where he learns of the existence of a deserter from

Napoleon’s army who had once terrorised the area,

and actually finds his hiding-place, a shack in the midst

of the forest. The narrator turns this makeshift shelter,

unrecorded by surveyors, into a place of retreat and

remoteness from the world that finally allows him and his

lover to escape the Allied bombardments.

Günter Grass said of Schmidt ‘I do not know any writer

who has listened so closely to the rain, so often talked

back to the wind and given the clouds such literary

surnames.’ The novel combines an erudite, terse cynicism

with grand, elated outpourings about the moors, the moon

and the wind. In formal terms it consists of a succession of

short paragraphs full of neologisms, plays of punctuation,

onomatopoeic nouns and coded references, in a ‘narrative

cascade’ of memories and fleeting glimpses arranged ‘as

if a spasm-shaken man were watching a thunderstorm in

the night’.

We can imagine how this way of writing in accordance

with ‘the lines of movement and the tempo of the

characters in space’, in which all is fragments and speed,

had a special resonance with Stephen Felton. Taking

this mysterious book, which he only knows in English

translation, he in turn presents a series of forms that do

not necessarily illustrate a particular passage, but instead

reflect a memory of his readings, his daydreams and the

dreamlike fertility of a literary experience.

Paul Bernard

Curator at Mamco

Translation, Kevin Cook